Governance

Governance issues surrounding herring are situated within larger issues surrounding the governance of all traditionally harvested resources.

Many First Nations assert that they have authority to harvest a fair share of resources from -- and be meaningfully involved with management decisions of relevance to -- their traditional land-sea territories. This assertion stems from their longstanding occupation and use of the land and sea, and from continuity in Indigenous management systems overseen by hereditary chiefs and other community leaders.

On the other hand, governments assert their authority through legal and political structures that have been evolving since the arrival of Europeans. In Western Canada, Provincial and Federal Governments did not recognize the territorial authority and interests of First Nations; this is why treaties were not historically pursued and why questions and heated debate about the recognition and implementation of First Nations rights and title to land-sea spaces and resources, including herring, continue today.

However, the Canadian constitution recognizes that First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people have unique rights grounded in their longstanding use and occupation of the land and sea. Consequently, the courts continue to affirm specific harvest, commercial and management rights to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis on a case-by-case basis.

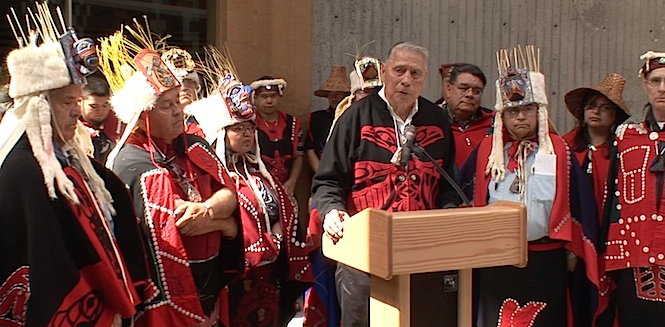

Heiltsuk Leadership. Photo: M.Wunsch